To understand how each spin master, technique, and industry contributed to the current state of disinformation in the U.S., it helps to know the history of how and why the PR industry was created.

In response to a protest, the country’s largest oil company sent in private security teams, who wound up killing several protestors, including women and children. The company’s spokesperson claimed the protestors were hired by a labor union trying to stir up trouble.

Sounds like it could have been written about any of a half dozen recent pipeline protests, right? But these are the basic details of a mining strike in 1914, in Ludlow, Colorado. The mine was owned by Standard Oil, and the Rockefeller family had only a few years prior been raked over the coals by a messy antitrust lawsuit and a series of investigative features about their monopoly on the country’s burgeoning oil industry.

They needed help burnishing their image, so they called on another industry that was just emerging at the time: Public relations. Ivy Ledbetter Lee, the first modern PR guy, came up with that idea that the protestors were hired agitators. Today we would call them “crisis actors” and it’s an accusation thrown at almost every protest, but few people know the whole thing was created by a PR guy working for an oil company back in 1914.

Lee invented all sorts of other tricks of the trade too. The press release, for a start. Before Lee, companies had a pretty adversarial relationship with the press and vice versa. Lee thought businesses would do better to tell journalists more of their story themselves. It was so unusual that when he first began sending press releases to The New York Times, the paper printed them verbatim. On behalf of rail, coal, oil and tobacco clients Lee also created seemingly independent information bureaus, like the Bureau of Railroad Economics, whose experts were regularly quoted criticizing railroad tax proposals. Again, this was more than 100 years ago. And Lee was followed by generation after generation of PR experts, each adding another bell or whistle to America’s disinformation machine—some on behalf of oil, others on behalf of the chemical or tobacco industries, often on behalf of all three at the same time.

For years, the story about disinformation has been that Big Tobacco created it all and then Big Oil copied them. And there's a thread of truth there. Some of the same phony scientists who sold America on the idea that smoking was safe turned around and told them not to worry about climate change. But it’s not the whole story. To get that, we need to look at the context that enabled climate denial to flourish, an information system polluted by 100 years of propaganda. And we need to look at who was hiring those phony scientists—not companies, but PR firms. When people focus on one particular form of science denial, or on one technique that this or that industry copied from another, this is the big picture they miss: the disinformation machine driving everything from QAnon conspiracies to climate denial, vaccine hesitation to white nationalism. It’s bigger than any one industry, but it was built on behalf of all of them, and if we want to have any hope of addressing the large, intersecting, complex problems facing us today, it must be better understood. And then reconfigured, or dismantled altogether.

***

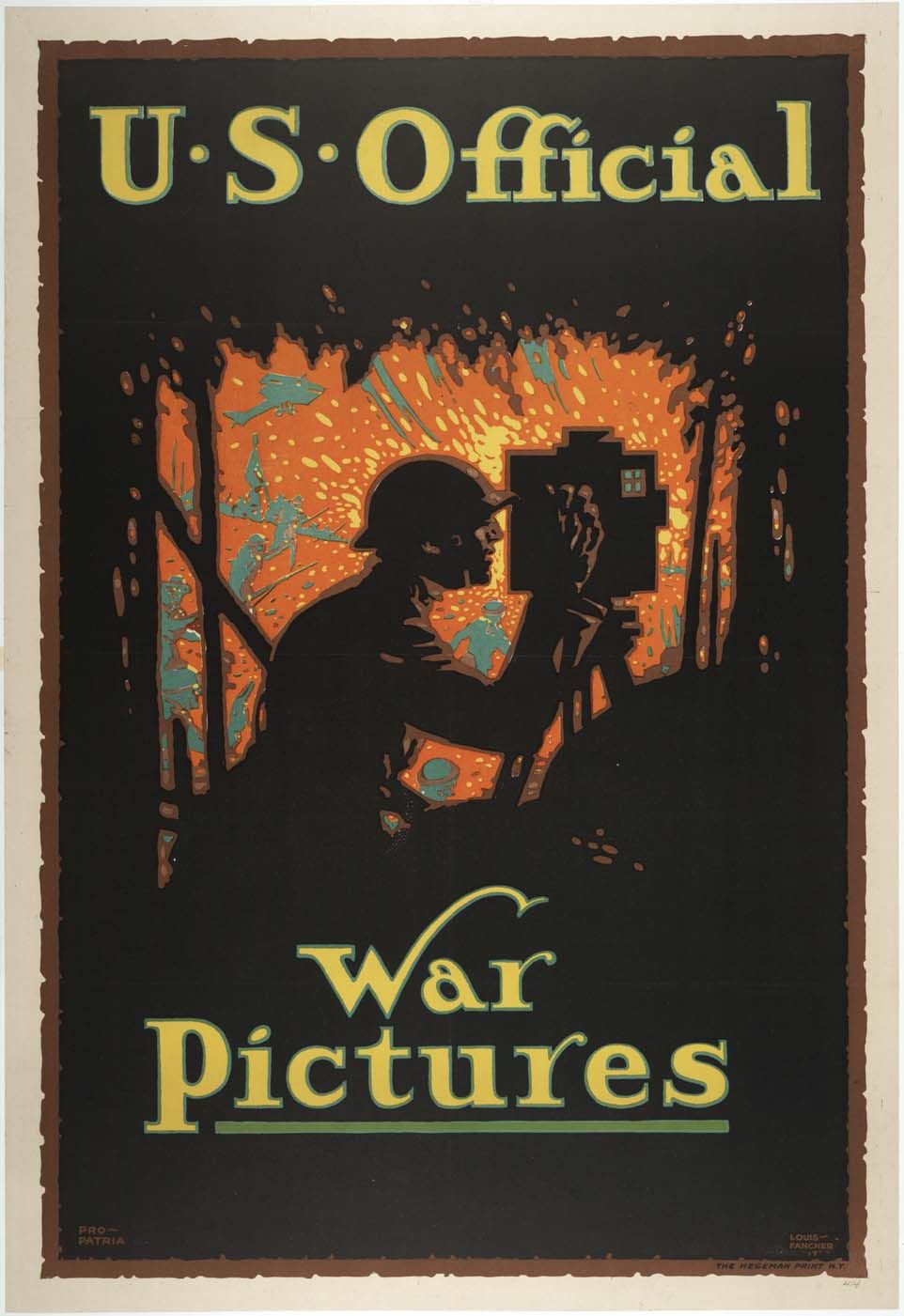

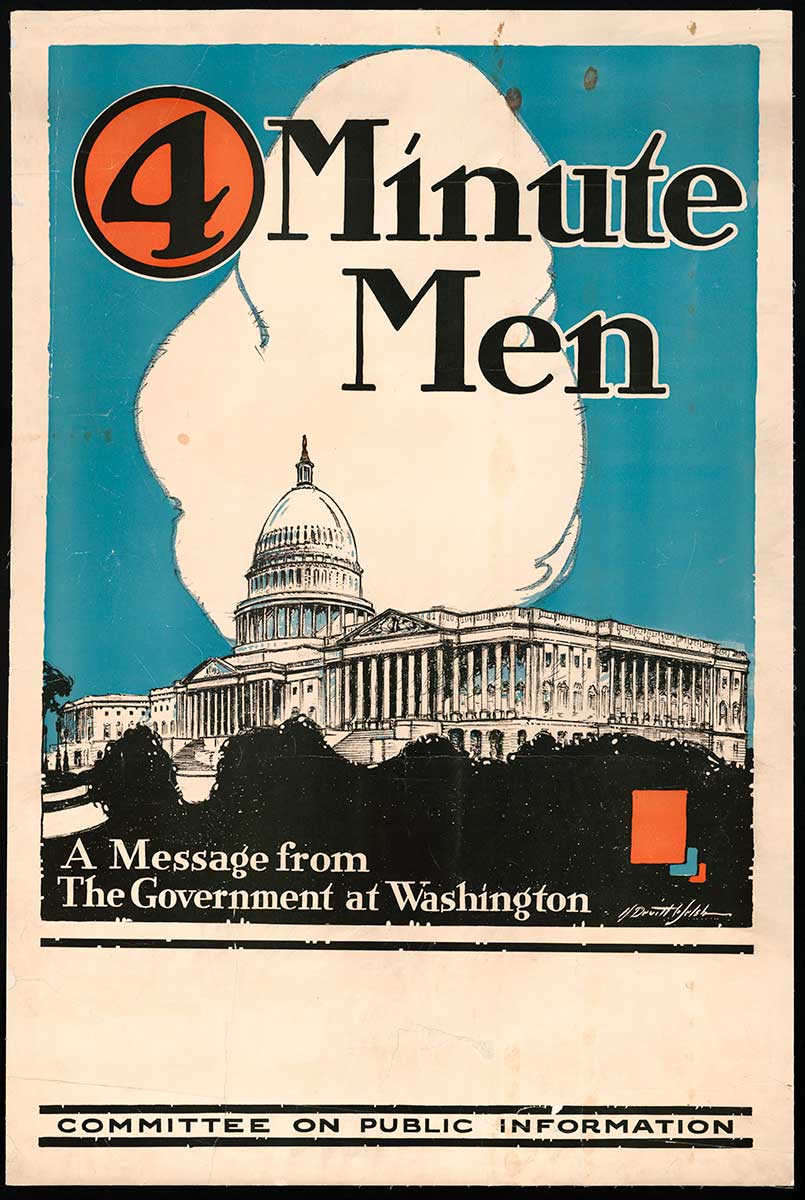

Just as Ivy Lee was building the modern PR industry, the U.S. government realized it needed a bit of propaganda to help sell American citizens on World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had made staying out of the war a key part of his campaign, and now he needed to convince Americans that it was a good idea to join in...without looking like a hypocrite. He tapped George Creel, a journalist turned political campaigner who had helped with Wilson's electoral bid, to build out what was eventually called the Committee on Public Information and generally referred to as The Creel Committee or the Creel Commission. Creel tapped some of the nation's greatest journalists (Ida Tarbell, for one!), filmmakers, artists, and publicity men to create a 360-degree assault on the American public. They made films, created compelling posters, and even launched the world's first "influencers." In cities and towns across the country, Creel and his team found influential members of society and trained them to give 4-minute pro-war speeches before screenings of silent films or big events. They were known as the "4-Minute Men".

Several members of the Creel Committee went on to be major influences on the burgeoning PR industry. One of them was a young publicity agent from the theater, Edward Bernays. Bernays had done some creative promotion of plays with particular social missions and had worked for major ballet companies as well, and his work caught the eye of Creel. It didn't hurt that Bernays's uncle was Sigmund Freud—on both sides, in a bizarre and some might say Freudian twist (Edward's mother was Freud’s sister, and Freud was also married to Bernays’ father’s sister). Bernays grew up in Vienna, hearing all about Freud’s theories on the deeply buried human impulses that drive behavior. While Ivy Lee was not part of the Creel Committee, he handled publicity for the American Red Cross during the war effort, and he and Bernays worked together often through their respective positions. Bernays became a trusted colleague of Lee's during the war, the only other PR guy that Lee thought his equal. It was after WWI that Bernays famously said, “If propaganda could be used so effectively in war, why could we not use it in peace?”

At the time, democracy was still a relatively new idea, and those in power were almost universally terrified of it. Propaganda—which Bernays later renamed “public relations” because “the Germans had given it a bad name”—was created as a reaction to growing public criticism of the titans of industry who had once been hailed as heroes. But it was also created to provide those in power with the tools to manipulate the masses. Bernays, Lee, and a client they both shared—Adolf Hitler—were all close readers of French philosopher Gustav Le Bon, who posited that the public, or as Le Bon put it “the crowd,” could only be both satisfied and safe when it was controlled. Like Le Bon, Bernays had a real disdain for the public, writing in his seminal book Propaganda:

Those who manipulate the unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government, which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested largely by men we have never heard of. In almost every act of our lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by a relatively small number of persons who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.

To be clear, Bernays saw himself as part of that “ruling power,” and he relished the role of manipulator.

Ivy Lee died fairly young, in his 50s, and when he did Edward Bernays inherited many of his clients, including both The American Tobacco Company and The American Petroleum Institute, the fossil fuel industry trade group that Lee had helped Standard Oil create as World War I was ending. While Ivy Lee largely focused on shaping and controlling the way the media got information as a way to mold public opinion, Bernays tried to manipulate the masses more directly. His best known trick was obliterating the taboo against women smoking in about six months, a feat he pulled off for American Tobacco.

They tasked Bernays with increasing sales, and he actually went to a psychoanalyst to talk about what cigarettes signified. You guessed it, phalluses. This got Bernays thinking about the “penis envy” women supposedly feel and an emergent push for women’s rights, and boom he had it: he would make smoking a women’s empowerment issue. He convinced a few young women he knew to stage a smoking “protest” in New York, calling cigarettes “freedom torches,” then alerted the press to the protest. It made headlines across the country and within a few months women all over the country were smoking and American Tobacco’s sales were soaring.

So, to recap, PR emerged as a way for industry to deal with a three-pronged threat: the rise of investigative journalism and activism shining a light on the misdeeds of industry, the emergence of regulation (which previously left industry to its own devices), and the expansion of the vote to members of society that had little in common with captains of industry. It was wildly successful. The first wave of PR effectively put a stop to the muckrakers’ early calls for corporate accountability.

Then the Depression hit and once again America’s bosses were the bad guys. Publicists like John W. Hill helped companies like American Steel paint labor unions, social security, and the New Deal as socialist. Hill paid commentators like George Sokolsky to write op-eds in newspapers and magazines, or join panel discussions on the radio, ginning up fear about these ideas. (At one point, Hill’s firm Hill & Knowlton was paying Sokolsky $40,000 a year to write pieces criticizing Social Security and the New Deal—that's a high six-figure salary in today's dollars). Hill would go on to mastermind the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC), a hub of science denial around smoking...that sounds an awful lot like the research bureaus Ivy Lee had set up some 40 years before. Not a huge shock given that Hill idolized Lee.

Hill’s client roster also included the American Petroleum Institute, Texaco, and Monsanto during those years, so it's no surprise that you see the same tactics deployed by TIRC then used by oil companies to combat rising concern over "the greenhouse effect" or by agribusiness to combat rising concern over GMOs. In fact Hill would have folks from the tobacco companies and chemical companies join the API, because he spotted ways for all three industries to work together—to lobby together for or against regulation, to trade strategies and ideas, even to create new products together. Without PR firms bringing them together, these industries and companies may have tended to stay in their own worlds, but the type of cross-pollination Hill enabled was hugely influential.

In fact it’s how the cigarette filter came about.

Cigarette filters are one of the reasons oil and gas companies were named defendants in the tobacco litigation of the 1990s. “When tobacco companies needed to assess the toxics in their cigarettes and in cigarette smoke, the people they turned to to do it were the oil companies,” says Carroll Muffett, President and CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law. Oil companies had been testing exhaust and refinery smoke for years because of the Clean Air Act, so they were the ones that had the sophisticated equipment and the knowledge to test for toxins in cigarette smoke.

“And when the oil companies reported back to the tobacco companies on the toxins they were in fact finding in that smoke, you know, what did they do with the information?" Muffett said. "Did they go public and say there's a massive risk here? No. They entered into joint enterprises, joint ventures with the tobacco companies to produce cigarette filters.”

Since the inception of the PR industry, its most expert practitioners have deployed a handful of techniques on behalf of multiple industries and really in service of all industry: to paint business as a good faith member of the community, to sway public opinion, to avoid what infamous PR guy Rick Berman calls "public judgement," and to create political will in their favor. But they weren't operating in a vacuum. In deploying these techniques on behalf of industry, they fundamentally shifted the information ecosystem in America.

Today, it's not just industries that want to avoid regulation or deal with a crisis who use PR techniques, it's everyone from your local county government to your favorite musician to the most earnest nonprofit. It's the filter through which all information flows to the public. Which doesn't have to be a bad thing, but it has certainly led to the information pollution we have in the U.S. today, where trust in journalists and experts is at an all-time low, the public is tremendously confused, people can (and do) just consume "news" that tracks with their opinions, and so on. To clean up that pollution, it helps to know how to spot these techniques. Our hope with this archive and its corresponding podcast is to help people do just that—not to make people even more suspicious of everything they see, or double down on getting their information only from one trusted YouTuber, but to pull the mask off a bit and help people find their way through the filters to the information they need to make important decisions about their lives.